Review: Think You Know Michalopoulos? Ogden Retrospective Has Surprises in Store

March 9, 2017 - John D'Addario, The Advocate New Orleans

When you close your eyes and picture New Orleans in your imagination, there’s a good chance it looks like a painting by James Michalopoulos.

His architectural portraits of French Quarter buildings, with their melting, woozy perspectives and vibrant colors, are as much a part of our collective psychic landscape as a streetcar gliding beneath a canopy of live oaks.

And his ebullient portraits of New Orleans musical legends say “Jazz Fest” as much as the Gospel Tent or a bowl of Crawfish Monica.

Of course, Michalopoulos’s work is familiar to most audiences through its seemingly endless reproduction via posters and prints — not to mention the many artists who have imitated his style over the past several decades.

But a new retrospective of the artist’s work at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art aims to correct that — and manages to reveal a much more interesting artist and body of work than you might expect.

Beautifully and thoughtfully curated by the Ogden’s Bradley Sumrall, “Waltzing the Muse” presents the artist’s work in sections devoted to his portraits, landscapes, and street scenes.

The title refers to the close relationship between Michalopoulos’s art and the music that both informs and permeates his views of his environment.

“Like almost everything in New Orleans, Michalopoulos’s painting practice is usually accompanied by music,” said Sumrall in a statement accompanying the show. “Painting becomes performative, and he waltzes his muse across every canvas.”

The gallery that introduces the exhibition and focuses on Michalopoulos’s portrait-based work serves almost as a mini-retrospective of his whole career.

The works in this section feature three large-scale paintings that served as the originals for some of Michalopoulos’s iconic Jazz Fest posters and depict several familiar New Orleans faces, including Fats Domino and Allan Toussaint. They have a presence and vibrance that even the most limited edition poster version can’t come close to.

But the more intimate recent portraits in the same gallery show a side of the artist you’ve probably never seen before.

Quietly enigmatic, works like “Traibolical” and “Double Take” are a world away from the swagger of the Jazz Fest paintings, and in particular show Michalopoulos’s surprisingly subtle mastery of his medium.

In such compelling company as the portraits, the French landscapes that fill the hallway in the middle section of the show are perhaps less interesting only by comparison — though they’re strong works in their own right, and further show off Michalopoulos’s technical skills.

Pay particular attention to the way the artist uses a palette knife to create his effects. The heavy impasto of works like “Color Swim” and “Clairement Clotmain” are practically sculptural in their multidimensional surfaces.

Many of the landscapes nearly venture into abstraction, making you wonder what would happen if Michalopoulos abandoned portraits and landscapes entirely and started persuing fully non-representational art instead. (The 20th-century painter William Baziotes, whose work bridged Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism and who is revealed in the notes accompanying the show to have been Michalopoulos’s uncle, might serve as an example.)

As wonderful as many of the portraits and landscapes are, they’re practically appetizers for the considerable visual feast that awaits in central and largest part of the show, which occupies the Ogden’s main fifth floor gallery and is filled with Michalopoulos’ most characteristic scenes of New Orleans streets, buildings and the occasional vehicle.

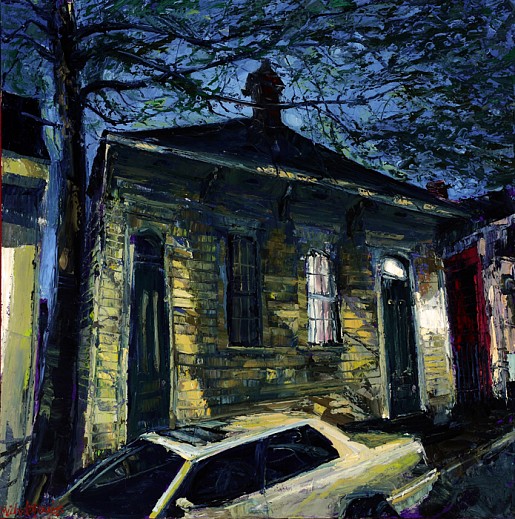

The atmosphere in these large-scale works is palpable. You feel as though you can walk right into a painting like “We Groovin” and feel the kind of French Quarter air that holds the sounds of buggy carts and music.

They also demonstrate Michalopoulos’ considerable talent in capturing the elusive effects of New Orleans light upon its built surfaces — an aspect of his work that almost always gets lost when it’s reproduced and something that his many imitators can never quite get right.

The distended perspectives that many lesser artists attempt to copy are also revealed here as less of a visual cliché than a crucial element of Michalopoulos’s masterful evocation of mood and atmosphere. And some paintings even hint at a kind of narrative, like the taxi idling before a building in “Marigny United”: who is it waiting for or who has it just dropped off?

You can spend a long time in “Waltzing the Muse” constructing your own stories to go with these evocative images. But perhaps the most exciting thing is seeing how Michalopoulos developed as an artist in the roughly 20 years he show covers.

Compare his earlier works like the portrait of Dr. John that opens the show to his newer portraits like “Not A Scintilla” or tours-de-force like “We Groovin” and “Swayed and Smiley.”

Many artists these days imitate the former. But the latter are uniquely Michalopoulos.

Back to Press